Consistency vs Coherence vs Atomicity

Before diving in the main topic of this post which is memory consistency and memory order, I’ll clarify some related concept and motivate the topic.

Consistency

Consistency or consistency model mainly specifies a contract between programmer and system on concurrent programming model. By specifying a consistency model, programmers will be guaranteed to obtain predicted results after reading, writing, or updating memory.

| (init) A = 0; B = 0 | |

|---|---|

| Thread 1 | Thread 2 |

| (1) A = 1; | (3) B = 1; |

| asm volatile(“”:::”memory); | asm volatile(“”:::”memory); // Prevent compiler reorder |

| (2) print(B); | (4) print(A); |

The above table demonstrates an example of memory consistency. Most programmer understand that compiler may reorder instructions to improve efficiency. The inline assembly ensures compiler not reorder (1) and (2) although they are not dependent. Due to the parallelism of different cores, it’s obvious the above code can print out different results based on execution order (10 - (1)(2)(3)(4), 11 - (1)(3)(2)(4)). However, can the code print out 00? (It seems impossible since it contradict to sequential program order.) Well, that’s what memory consistency model defines. In modern architectures (x86, arm), the answer is yes, 00 is possible. More details will be elaborated in the following sections.

Coherence

Coherence is also used to define behavior of read and write to a shared memory system. As the other post I wrote for cache coherence, the shared memory system can be a modern multi-core chip which has local L1/L2 caches for each core. Or it can be a distributed system which has multiple cached copies on different nodes with the same storage backend. However, the core difference between coherence and consistency is as quote in Wiki, Coherence deals with maintaining a global order in which writes to a single location or single variable are seen by all processors. Consistency deals with the ordering of operations to multiple locations with respect to all processors.

Basically, coherence usually deal with the smallest granularity of read and write to memory system. For example, for cache coherency, we only care about cache line size (64B). However, in software point of view, we see coherence in load/store granularity (1B/2B/4B/8B) since generally we don’t deal with load/store on more than 8B size. This actually leads to the next concept we want to talk about which is atomicity. Since the hardware (cache system) support 64B granularity coherence, does it mean we can guarantee 16B memory to be coherent?

Atomicity

Atomicity is an important database concept which defines indivisible and irreducible series of database operations such that either all occurs, or nothing occurs. In memory system, the database operations can be replaced with memory operations (e.g. read write). As I mentioned earlier, consistency model mainly deal the concurrent programming model. If we borrow atomicity concept from database field, we can gracefully solve the concurrency problem (memory ordering or memory consistency, synchronization, etc.). This is what transactional memory offers. However, this requires both programming model and hardware changes to support.

Why it matters in real life?

The above snippet is kind of unrealistic. Here, we show some real world examples to demonstrate the importance of memory consistency.

Memory consistency determines the possible memory orders for a sequence of memory accesses (CPU pipeline operates on smaller granularity than cache line size, besides, we don’t have semantic such as transaction to enforce atoimc). The below examples basically shows where memory order really matters.

Device operation

Consider a PCIe device with a DMA engine inside. When the driver initiate DMA operation, it needs to write several memory locations (registers inside the device). Consider the memory-mapped region are un-cached and we don’t need to issue clfush(). For example, direction, start addr, transfer size, trigger. These accesses must follow certain order constrains (trigger must happen at last).

Synchronization primitives

Synchronization is the building block of concurrent programming. Most architectures use atomic instructions to support synchronization primitives such as lock. Consider the following lock implementation using test-and-set instruction.

struct spinlock {

int locked;

};

void lock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

while (test_and_set(&lock->locked));

}

void unlock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

lock->locked = 0;

}

From the CPU pipeline perspective, atomic test-and-set means uninterruptible and atomic load and store pair. However, consider the very first example that motivate the memory consistency concept. Is it possible that two CPU cores both set (write) the locked variable? (This will be elaborated on the hardware perspective of memory ordering). The answer is definitely no. The atomic instructions actually imply memory ordering. For instance, the set part of the test-and-set will enforce visibility to all cores before test. (This actually depends on architecture, x86 LOCK prefix ensure atomicity and implies memory barrier, arm and other architectures maybe different.)

Hardware perspective of memory consistency

Why modern allow such memory consistency model (x86 uses total store ordering (TSO) consistency model, ARM uses even relaxed memory consistency model) that allow printing 00 in the very first example? The reason is of course performance consideration. It will make the memory performance so slow to maintain a programmer intuitive sequential consistency model.

Out of order execution for memory access

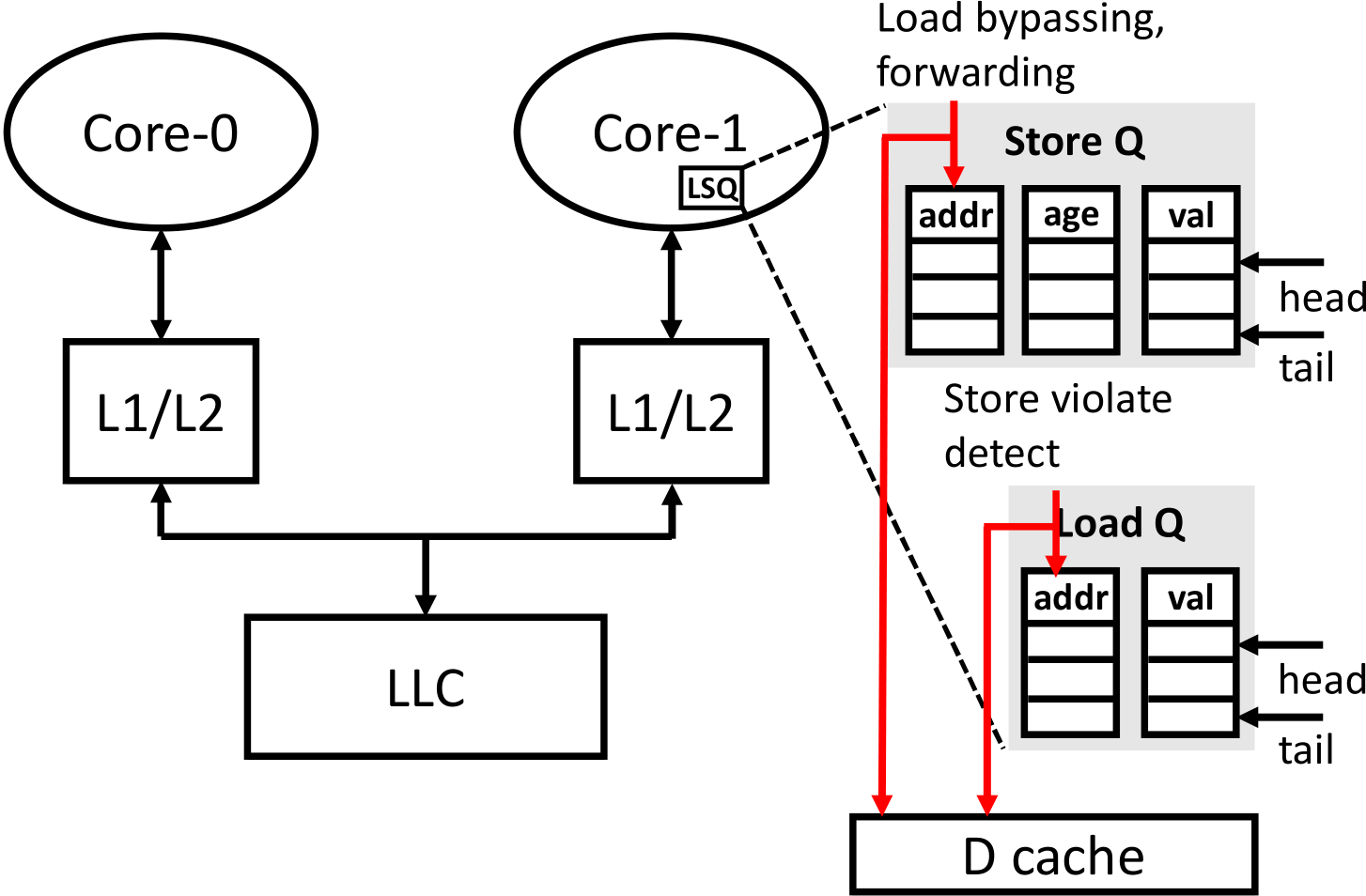

Figure 1 demonstrates the microarchitecture for out-of-order load/store execution. Such architecture ensures maximum IPC for load and store instructions while violate strict sequential memory consistency compared to in-order load/store execution (execute load/store by program order). Load/store queue (LSQ) provide the possibility of parallel and speculative execution of load/store instructions. Load bypassing and forwarding will examine store queue and cache in parallel to check dependency and fulfill dependent read after write (RAW). Store instruction also examine load queue after the store address is computed and detect potential load address conflicting (load can be speculative, i.e. issue before previous store address is resolved, since memory alias is rare).

|

|---|

| Figure 1 Load/Store queue for out-of-order execution |

The out-of-order execution of load/store instruction make it possible to reorder independent memory access. In the first example of the post, (1) and (3) can be executed before (2) and (4).

Store buffer and invalidate queue

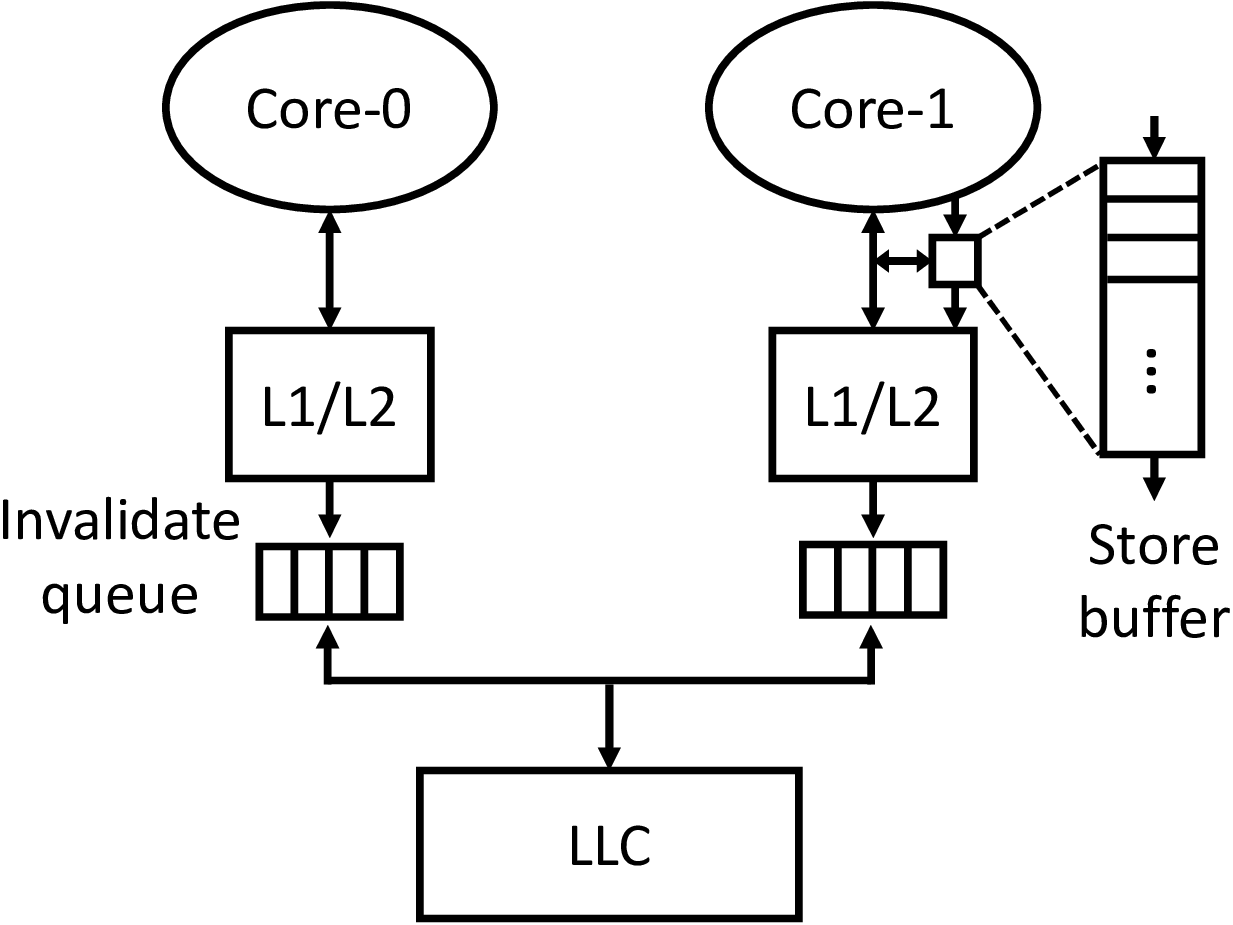

Figure 2 illustrates the other two important modules in core and memory system which are store buffer and invalidate queue. Unlike store queue, the store buffer contains the writes after store is retired or committed. The store buffer can coalesce (combine) writes since store size is generally smaller than cache line size. Besides, store buffer can hide the latency between core pipeline and L1 cache (cache miss can be long latency.) Similar to store buffer, invalidate queue between private cache and LLC stages the invalidate message of each write to private cache and immediately acknowledge to store buffer to prevent the blocking on store buffer and the core pipeline.

When writes are staged in store buffer, other core cannot see it through the caching system. Thus, affecting the memory view or ordering on the other cores. The item in invalidate queue also prevent invalidate stale cache lines to the cores. A load on the core may read the staled value (that is already overwritten by other cores) due to the invalidate queue. These two structures also add complexity to the memory consistency model.

|

|---|

| Figure 2 Store buffer and invalidate queue |

Memory barrier

In order to enforce memory ordering, the CPU provide memory barriers to ensure order for certain memory accesses. A write barrier or sfence will wait all previous stores retire and flush the store buffer to make sure all other cores view the previous store instructions. Similarly, the read barrier or lfence will wait all previous loads retire and flush the invalidate queue of its core to make sure the following loads read the latest data from its private cache. Noted, once the invalidate queue is acknowledged or dequeued, the coherence logic will enforce coherence for the entire cache system.

Memory consistency models

In this section, I will briefly introduce some consistency models in modern architectures.

x86

x86 use a pretty strict consistency models (total store order, i.e. TSO), meaning it won’t reorder load/store instructions much. The only possible reordering is read after write (RAW), which means stores can be reordered after previous loads.

ARM & Power

ARM and PPC on the other hands, uses a pretty weak memory consistency model, meaning it can basically reorder any independent loads and stores. This adds heavy burden to the programmers since they need to keep in mind the memory dependency all the time (when ordering matter).

RISC-V & SPARC

RISC-V and SPARC provide different memory consistency models from strict (TSO) to more relaxed model, like the weak model ARM uses.

Reference

https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~bornholt/post/memory-models.html

https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/memory-barriers.txt

https://mysqlonarm.github.io/Understanding-Memory-Barrier/