Synchronization is an important issue in computer system since multi-task paradigm begins. Synchronization becomes more of an issue with the rise of the SMP (Symmetric Multi-Processing) systems. (Notice, even in single core processor, synchronization is required. When thread is scheduled, the register is saved which may cause an stale value for a shared variable). SMP systems add one more complexity of the cache coherence subsystem which also impact the synchronization performance. In this post, we’ll discuss some architecture and software supports for synchronization implementation.

There are many use case that requires synchronization. First case is mutual exclusion scenario, for example, locking, atomic operations, transactions, etc. Second case is scheduling, such as consumer and producer problem (this may require OS level synchronization primitive such as monitor and semaphore). In this post we mainly discuss lower level synchronization primitive, i.e. spinlock.

Architecture/Hardware supports

The naive thoughts of implementing a lock will be using load-test-store logic. However, for most of the processors, the naive load-test-store is not atomic which requires multiple instructions. So, the most efficient approach to support synchronization is on hardware side. For modern processors, there are main for types of atomic instructions.

-

Test-and-set (BTS): Write 1 to memory location and return the old value in an atomic fashion.

-

Compare-and-Swap (CAS): Compares the contents of a memory location with a given value and, only if they are the same, modifies the contents of that memory location to a new given value. Also, the whole operation is atomic.

-

Fetch-and-add (FAA): Atomically increments the contents of a memory location by a specified value.

-

Load-link and store-conditional (LL/SC): Load-link returns the current value of a memory location, while a subsequent store-conditional to the same memory location will store a new value only if no updates have occurred to that location since the load-link.

spinlock using BTS

struct spinlock {

int locked;

};

void lock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

while (test_and_set(&lock->locked));

}

void unlock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

lock->locked = 0;

}

spinlock using CAS

struct spinlock {

int owner;

};

void lock(struct spinlock *lock, int tid)

{

while (compare_and_swap(&lock->owner, 0, tid));

}

void unlock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

lock->owner = 0;

}

Software aspect of synchronization

The core building block of synchronization is through the above atomic instructions in architecture or hardware level. However, there are also issues which requires special software optimizations for more efficient synchronization implementations.

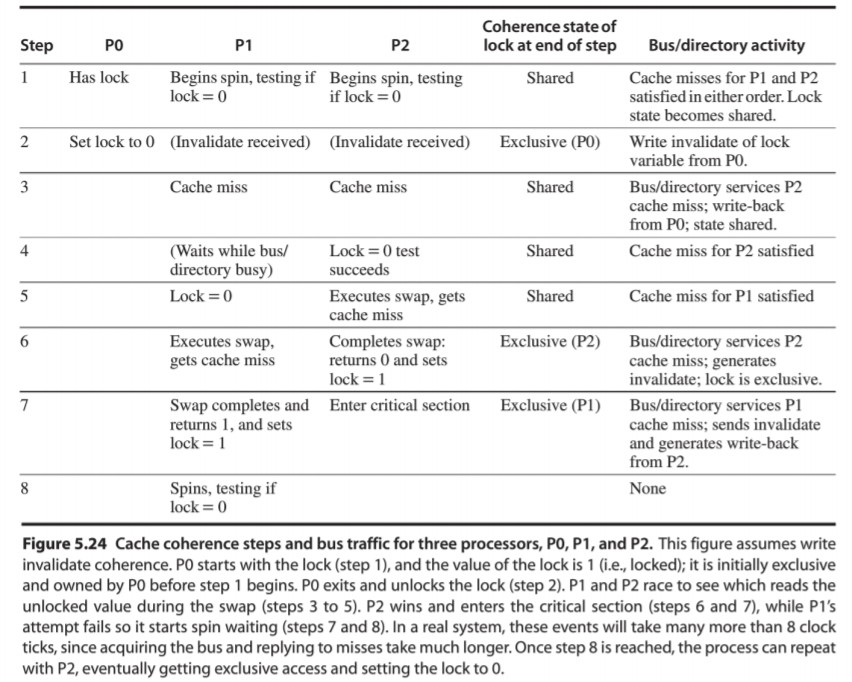

Test-test-and-set

For example, the above spinlock using test-and-set instruction will lead to high memory traffic in SMP systems. The problem is related to the cache coherent subsystem. Usually, in cache coherent protocol there are modified or eclusive state. The test-and-set instruction will constantly write to memory location from the cores acquiring the lock which will issue lots of invalid traffic to the core interconnect. Apparently, the CAS implementation of spinlock will reduce the coherence traffic. However, another way to mitigate the memory traffic for test-and-set is called test-test-and-set. The idea is load the locked variable first and spin if the locked variable is not zero without issuing the test-and-set instruction. So, during locking time, the locked variable will stay in shared state which doesn’t require memory traffic. Only when, the previous thread release the lock, other threads will issue the test-and-set instruction to compete the lock.

The enhanced spinlock implementation is as follows:

void spin_lock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

while (lock->locked || test_and_set(&lock->locked));

}

The following figure demonstrates the cache coherence state transition for spinlock acquire/release.

|

|---|

| Figure 1 Cache coherence state transition for spinlock |

Ticket spinlock

Another aspect of spinlock performance except for memory traffic is wait time (avoid of starvation). For the previous spinlock implementation, either using BTS or CAS, once the thread holding the lock exit the critical section, all the other threads will need to compete the same lock equally which may lead to one thread wait for lock for a long time in certain cases. To resolve this issue (guarantee fairness), we can use the FAA instruction to implement ticket spinlock.

struct spinlock {

unsigned int next_ticket;

unsigned int now_serving;

};

void lock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

unsigned int my_ticket = fetch-and-add(lock->next_ticket);

while (lock->now_serving != my_ticket);

}

void unlock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

lock->now_serving++;

}

Array/Linkedlist based spinlock

The above ticket spinlock has a scalability issue. Releasing the lock need to modify the shared counting variable which will lead to heavy invalid traffic to the coherency subsystem. To solve this problem, we can use space trade off by let each CPU has its own cache line for indication of the lock. (there will be one counting shared variable, but only lead to 1 to 1 CPU communication). Below shows the example of how array based spinlock is implemented.

struct spinlock {

unsigned int status[P]; // 0-locking, 1-wait

unsigned int head;

};

unsigned int my_element

void lock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

my_element = fetch-and-add(lock->head, 64);

while (lock->status[my_element] == 1);

}

void unlock(struct spinlock *lock)

{

lock->status[my_element] = 1;

lock->status[my_element + 64] = 0;

}

On releasing the lock, there is only 1 invalid message passing from the thread releasing the lock and the next thread which will acquire the lock (much like the ticket spinlock).

Spinning vs Blocking

For larger granularity system level lock primitive such as mutex, monitor, etc. What it probably does is to spin first and then block (schedule through context switch). Unless you really know what you are doing (fast switching), using this hybrid approach can be both CPU efficient and high performance.

Reference

https://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/academic/class/15418-s12/www/lectures/19_synchronization.pdf

https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/133445693

http://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs4410/2015su/lectures/lec06-spin.html

http://www.cs.tufts.edu/comp/140/lectures/Day_21/Synchronization.pdf

https://inst.eecs.berkeley.edu//~cs252/sp17/lec/CS252-Sp17-Lec15.pdf

https://compas.cs.stonybrook.edu/~nhonarmand/courses/fa17/cse306/slides/11-locks.pdf